A page for short answers to all sorts of questions children may have about Sumer!

Parents, Teachers, feel free to ask your own questions.

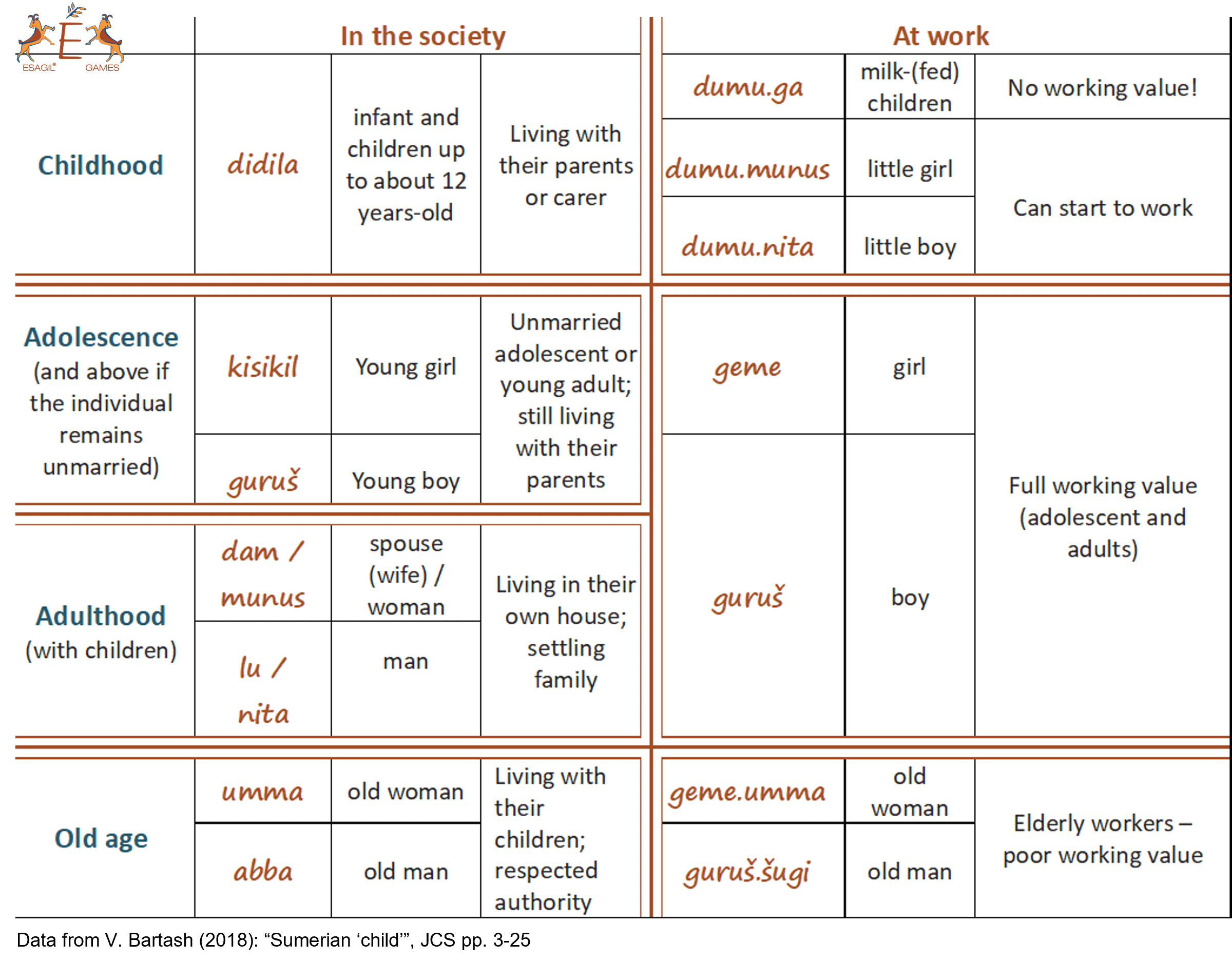

When did Sumerians get married? When were children thought of as adults?

As in many traditional societies, marriage (and the birth of the first child) is central in Sumerian society to determine the passage from youth to adulthood for both women and men. They probably were getting married quite young… as soon as they could have children. But we do not know at what age exactly, because Sumerians do not count their age in years.

People place themselves in the society according to age grades, mainly related to having children or not on the one hand and to their ability to work on the other (relevant to administrative documents).

What were the roles of men, women and children in the family?

Some texts let us suppose that a competent woman ensures stability in the household and manages it efficiently. But this task is not necessarily limited to housework and raising children: it also means, in some cases, doing business and running an estate. The father is responsible for the well-being of his household, and all children remain under his authority until they get married themselves. The main role of the children (didila) probably is to help their parents in all kinds of daily activities. Boys (and maybe girls) also go to “school”, a private house in the same district. Their teacher probably is a scribe: they learn how to write and also maths.

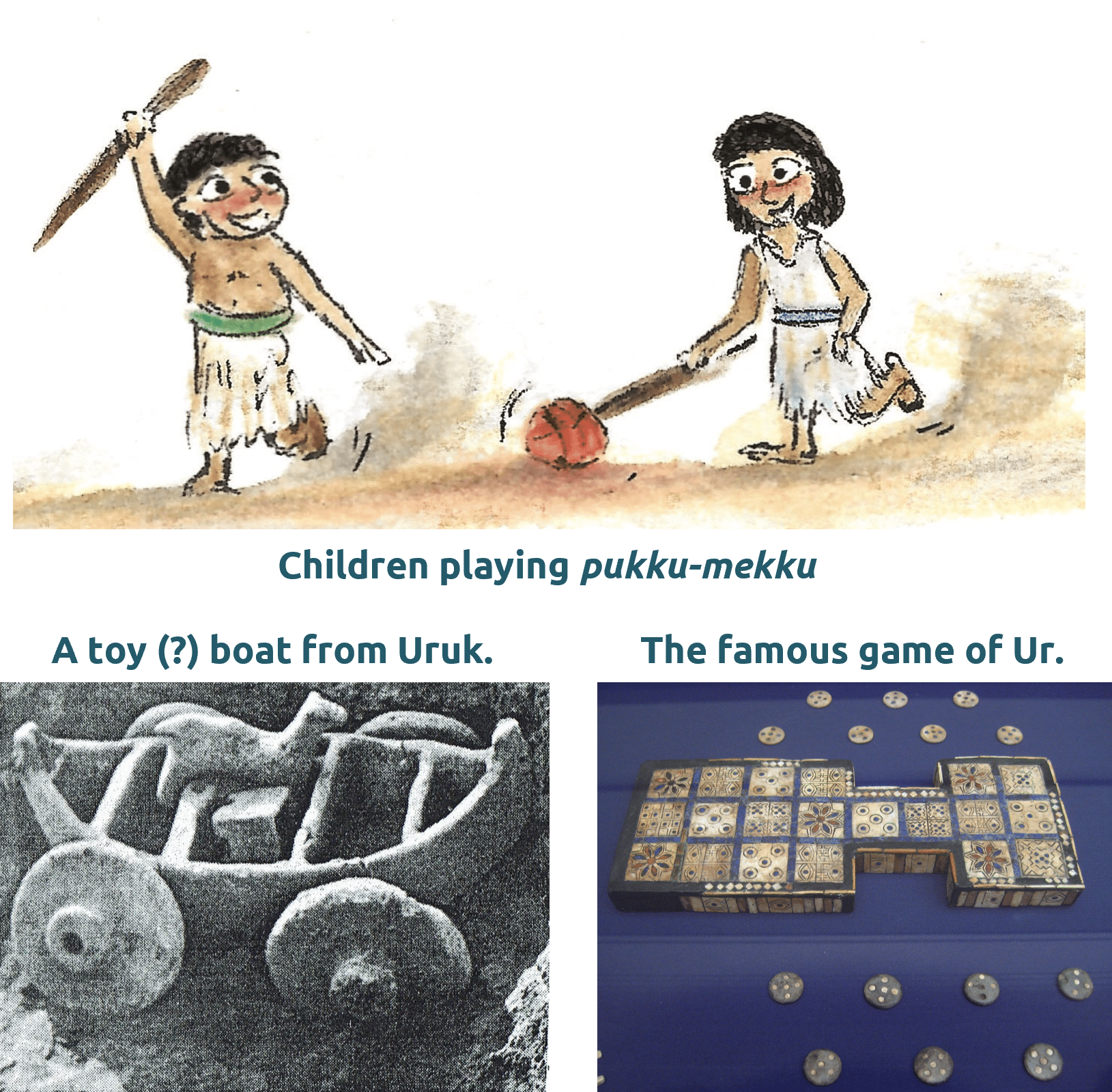

What kind of toys did children play with?

So, many children probably did not have much time to “play”. We do not know much about their games and toys because texts do not talk much about childhood. Yet, we do know one game, pukku-mekku, that may have been some kind of ball-game (but some scholars now suggest it was a board game!). Archaeologists also found in excavations models of chariots or boats on wheels to pull around. Children also probably had wooden toy weapons and dolls made of reed and rags for instance, but we have no traces of them.

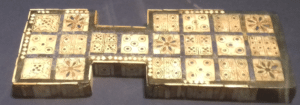

For teenagers and adults, the board “game of Ur” is famous, and probably was quite popular, as several copies have been found. The rules have been reconstructed by scholars, and we can still play it!

Can you tell me about Sumerian marriages? Do any of their marriage rituals makes their way into other civilizations?

We don’t know much about rituals of marriage in Sumer in particular or in Mesopotamia in general. Texts dating from the second millennium BC (after the Sumerian period) tell us that the bride is covered with a veil on the day of her wedding, to indicate her new status as a married woman (aššatum in Akkadian). She should remain veiled as long as she is married. According to some sources, the groom pours oil on the head of the bride during the ceremony. But it remains difficult to say for sure whether this usage was common or confined to wealthy families, and whether it was widespread or not.

After the Sumerian period, texts (contracts, letters, law codes) much insist on the exchange of gifts between families to seal the alliance between them. The bride brings a dowry from her father’s house (šeriktum in Akkadian) and the groom, a gift (terhatum in Akkadian). It is possible that this gift originally consisted of food and drinks for the wedding feast.

Marriages were monogamous. However if the wife could not have children, her husband may then take another spouse. The first spouse remains higher in rank.

Were women considered property of the man, did they have rights?

Women depend first on their father and elder brother, then on their husband after the wedding. But they were not men “properties”; they had some rights and some were very independant.

Divorces were possible and women could leave their husbands on their own will, even if to return to their father’s house:

“If a woman rejects her husband, and says “you don’t behave like a husband!”, then her case will be examined by the neighbours: if she is behaving correctly [if she is chaste and is not faulty] while her husband keeps going out and treats her badly, that woman is innocent, she will take her dowry and will go back to her father’s house.” (Hammu-rabi law code §142)

Law codes tell us a lot about marital relationships and “women rights”.

Series of questions about Sumerian houses – following the session “My house in Sumer” (Year 5 – Spinney; Years 5 and 6 – Les Petits Caméléons)

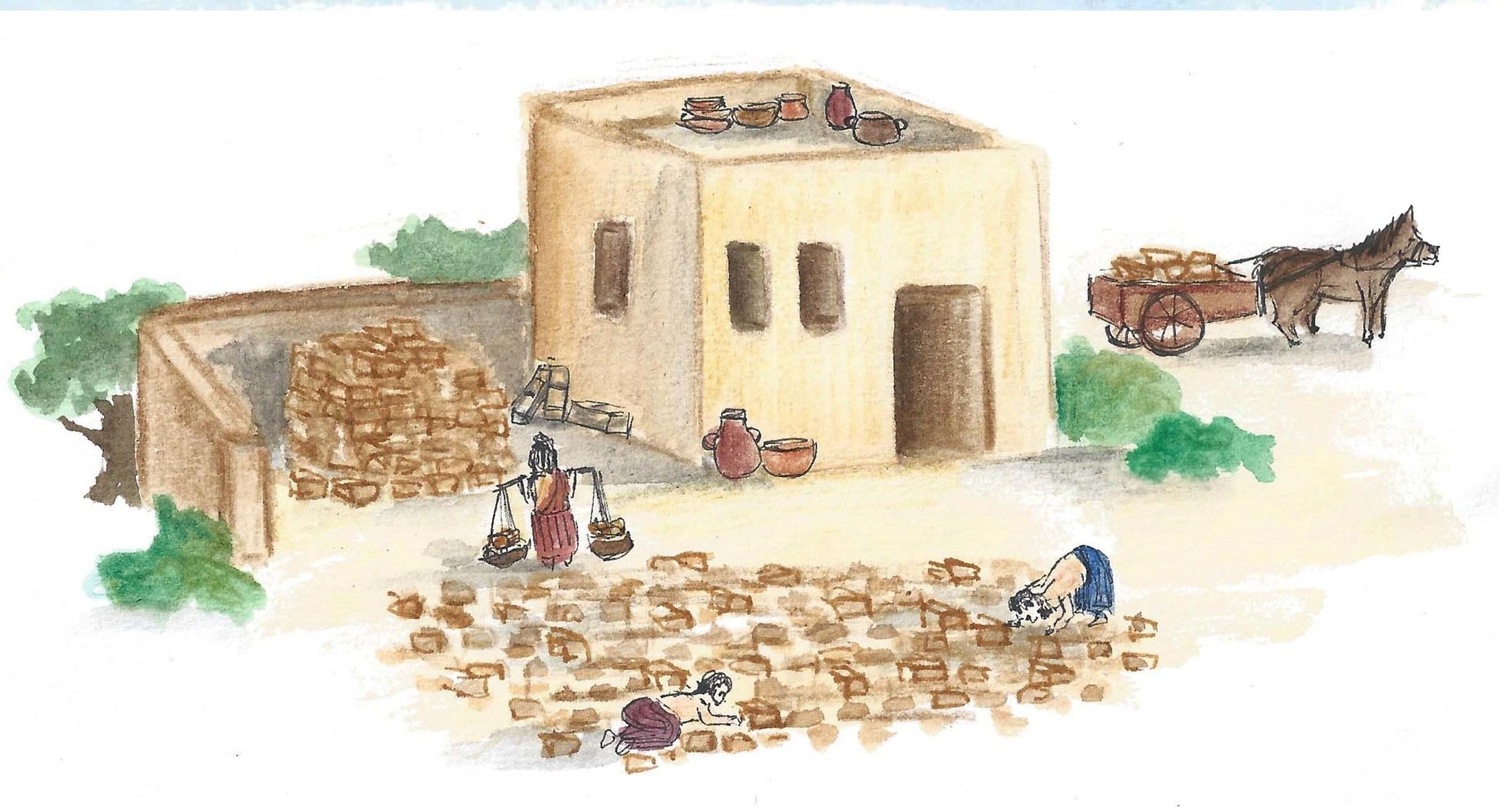

Why don’t they use stones to build their houses?

Sumerians use mudbricks to build their houses (and every other buildings) because there are no stones in the Land of Sumer – it is a desert steppe.

On the other hand, mud is an unlimited raw material, cheap and convenient. Bricks were made of earth, water and chopped straw (to give them some consistency); the mixture is “moulded” in a rectangular wooden frame, and left to dry in the sun.

The only problem with mudbricks is that it deteriorates fast: the houses need to be kept in good repair and to be well protected by plaster that covers the outer walls. If not, the walls will “melt” in the rain, and the house will fall in ruins… This is one of the reasons why so many Mesopotamian buildings have disappeared: as soon as nobody maintain them, they crumble back to earth.

What if there are very small holes in the walls and the rain can go through them?

Sumerians put mud plaster or lime plaster on their outer walls to protect them. When they were building the walls, they also paid much attention to the fact that the joints between bricks would not coincide. On top of this, they put (clay) mortar in the joints.

There were no holes in the walls of a Sumerian house, and the walls would not fall under the rain, unless there is a huge storm.

But do they have windows ?

Yes. Usually rectangular ones, and they were very small. All the best to keep the walls safe and to protect the inhabitants from the heat.

How often do they have to repair the plaster on their walls?

Very good question! Regularly, at least once a year, maybe twice a year, because plaster is so essential to protect walls. Plaster is made of lime, gypsum or mud. Mud plaster is used for common houses. Lime or gypsum plasters are used in more refined houses or monumental buildings: it is white and it can be smoothed or polished, even painted.

What are the roofs like?

Roofs are flat. They were made of palm trunks covered with (reed) mats and layers of mud, each closely and firmly tight to make the whole waterproof.

Only temples and palaces were roofed with imported timbers.

Do Sumerians go to school? (Year 5 – Spinney primary school)

Sumerians were going to “school” to learn the cuneiform writing, the Sumerian language and mathematics! But not all of them were going. The school was called “house of the tablet” (é.dub.ba), even though it was not a building in itself: teaching was given in private houses to a small group of children. Such schools have been excavated in the cities of Ur and Nippur, for instance. The houses might be identified as schools when some types of school tablets are found in them, such as round clay tablets on which the young scribes were writing their first cuneiform signs.

Why do they write on an object that nobody can see? (year 5 – Spinney primary school)

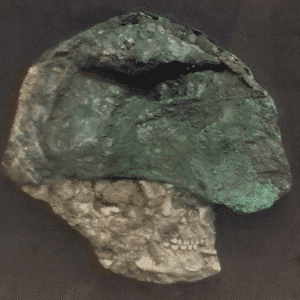

Building a temple was one of the main duties of a Sumerian king. Numerous inscriptions tell us about kings building temple(s). Some of them were on the walls or on statues, but others were written on objects buried in the foundations or on nails hammered in the walls.

These were for the gods, as proofs or reminders of the identity of the king who has built the temple. Hence, the kings made sure that the gods will remain favourable to their kingdoms. These inscriptions often ended with a curse: the best way to dissuade any ennemy king to destroy the temple.

Are there horses in Sumer? (Emily - year 4)

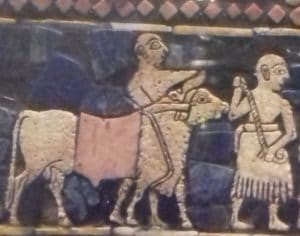

Horses are known to Sumerians: they call them “donkey of the mountain” (anše.kur.ra). But horses are from Anatolia and Iran, where they were first domesticated probably around the IVth millennium BC. There were no horses in Sumer until the very end of the period during the so-called Ur III dynasty. Even then, they remain rare. A text that lists various kinds of the horse family in a city’s farms counts 38 horses for 2,204 donkeys. The donkey was by far most popular in Sumer: charriots were donkey-drawn and kings were riding donkeys.

Did ancient Mesopotamians keep cats as pets?

Not really. They don’t tell us much about cats. Cats were not as important as they were in Ancient Egypt for instance, only good at catching mice! They are not often mentioned in the texts, but appear in lexical lists. On the other hand, Sumerians probably had dogs.

Didn’t they also have domesticated aurochs? A now extinct kind of ox?

Sumerians did distinguish wild bulls (Sumerian: am) and domesticated ones (Sumerian: gu4). It is possible that their wild bull is the auroch (Bos primigenius) from which domestic cattle (Bos taurus) may have emerged. There also were zebus and water buffalos in ancient Sumer. Cattle were first domesticated in Anatolia (modern Turkey) around VII-VI millennia: in the neolithic site of Çatal Hüyük, horns of bulls were hung on the wall.

Several kinds of domestic bulls were characterized in Sumerian texts: gu4 is the generic term, but gu4-apin may well refer to an ox (lit. “the bull of the plough”). In some circumstances, they also classify them according to their coats (speckeled or not) or their diets (barley or grass for instance), and also distinguished low-fat ones to very-fat ones.

The wild bull is one of the mightiest animals next to the lion. The famous Gilgameš once defeated the powerful Bull of Heaven (the constellation Taurus) sent by the god Enlil to destroy the city of Uruk. Kings are often compared with either a bull or a lion.

About two millenia later, Assyrian kings are hunting wild bulls as well as lions to enhance their own strength. In one of his inscriptions, the king Aššurnaṣiparl claims to have killed 40 wild bulls and to have captured 8 of them alive, who were then kept in his wonderful parks.

How do Sumerians bury their kings? (year 5 – Spinney primary school)

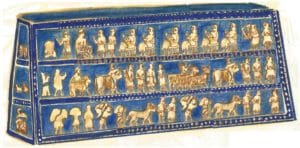

Sumerians do not build pyramids for their kings. Only few royal graves have been unearthed: the most famous ones are from Ur, and date from the Sumerian period (ca 2500 BC). More than thousand graves were excavated in the so-called Royal Cemetery of Ur, but only seventeen of them were considered as royal tombs because the material they contained was exceptionnaly rich. Two kings, Akalamdug and Meskalamdug, and one queen, Puabi, have been identified. In two of the tombs, there were evidence of human sacrifice: 74 servants were buried with their master (king?) in the “Great Death Pit” and in the “King’s tomb” soldiers with their weapons together with ox-driven charriots and 50 more servants, both men and women, were buried with the king. This practice is unparalleled in Mesopotamia.

What were they doing in the ziqqurrat? (year 5 - Spinney primary school)

Nothing! The ziqqurrat was a plain building: things were happening only on the steps and in the temple at the top. However we are not sure either on what was happening up there. See here for more about the ziqqurrat.